It’s perhaps not surprising that bike-sharing was born in one of the world’s most prolific transport innovators. France brought us the stylish automobiles of the 1960s, high-speed TGVs, Airbus jetliners – and urban bike-sharing.

40 years ago, the French city of La Rochelle launched what is considered the world’s first successful bike-sharing programme, Vélos Jaunes (Yellow Bikes). Incredibly, the bikes were actually free to use at first, and 30 years later ( in 2004) the fellow French city of Lyon would launch the world’s first major bike-share scheme using next-generation, computerized bike racks and memberships cards.

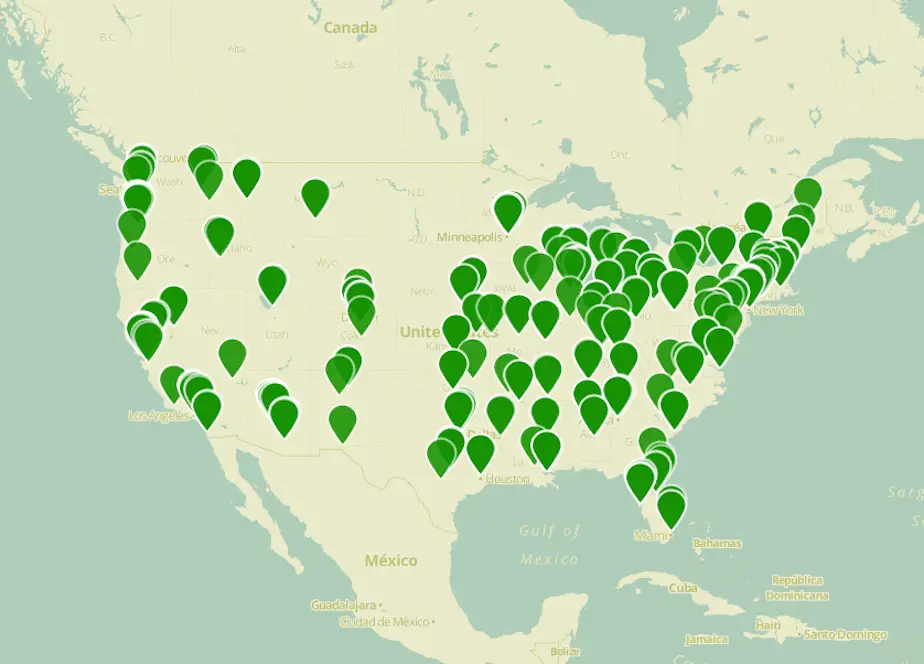

More than 500 cities around the world now have a bike-share system, most of them being wildly successful in terms of market penetration and user-rates. In fact, we’re positively hooked on them.

New York City’s own Citibike was launched earlier this year and in only a few months the programme has already grown to nearly 100,000 members. User numbers aside, however, the vast majority of these systems have floundered financially, much to the dismay of city governments. But can (or should?) bike-sharing be financially self-sustaining?

Some rightly point out that there is hardly any public transport system in the world that can cover their expenses with rider fares alone and nearly all benefit from some sort of government subsidy. Some, like New York City Transit, cover less than half their expenses with fares.

While we needn’t rehash all of their social, health and environmental advantages here, there is clearly a strong argument to the public benefit of bike sharing systems. They are as much part of the urban landscape as sidewalks and city parks, so why aren’t we treating bikes to the same generosity (at least willingly) as we would with other public “goods”?

The answer might be growing public debt, neoliberalism and the decline of collectivist ideals. Maybe. Perhaps bikes still aren’t perceived to be a serious form of transport, but rather a leisure activity, and therefore not something likely to contribute to the economic success of a city.

Whatever the answer, cities around the world are scheming desperately to turn bike sharing into profit and something that doesn’t appear to be tugging at public purse-strings.

Well if profitability and financial sustainability is the goal, then Paris wins hands-down. Built in 2007 and now the largest bike-sharing system outside of China, Vélib (a play on the French words for bicycle (Velo) and liberté) has over 16,000 bicycles and an astounding 1,200 rental stations.

And not only is it one of world’s most successful in terms of user-rates, with 20 million rides in the first year alone, it’s also one of the only to be netting healthy profits for a city, to the tune of $30 million (€20m euros) per year.

Compare that to Barcelona’s Bicing, also launched in 2007 but now running an annual deficit of around €12 million. London’s system lost $21 million in 2012 and is expected to cost more than 5 times the sponsorship revenues in the next two years. New York’s privately run Citibike is by some accounts a financial flop in need of tens of millions of dollars of investment. Montreal’s system, Bixi, which went on to export itself to two dozen cities around the world including Toronto, New York, Melbourne, London, and Washington, has gone bankrupt and is still awaiting rebirth. And it’s not the only one to have met its demise.

So what’s the key to Vélib’s success?

The idea behind their financial success may be unashamedly capitalist, but it is also surprisingly creative. The city enlisted the help of an advertising agency, JCDecaux, to build and manage the entire system for 10 years in return for exclusive rights to 50% (or around 800) of the city’s advertising billboards.

While JCDecaux pays for the costs, the city rakes in all the revenue, including a €3 million annual fee, amounting to €20 million every year. We can only assume the deal is profitable for JCDecaux, as they have remained committed to the programme and have expanded the model to other cities globally, although none as large as Vélib.

While some systems are open only to residents, Vélib has taken advantage of the tourist trade (Paris receives some 44 million tourists a year) which has undoubtedly helped spur success.

But Vélib has faced hurdles too. It’s estimated that 80% of the original bikes have been destroyed or stolen, with many having ended up in the Seine, or abroad. The city recently reached an agreement to pay the €4 million annual cost of replacing and repairing vandalized bikes, eating into its profits. Academics have linked much of the vandalism to inequality in the city, with the attrition being blamed on angry youth who see Vélib as the domain of the more privileged middle class.

JCDecaux, for its part, has been more progressive in terms of lowering costs for itself. While Barcelona’s Bicing incurs immense costs moving bikes by truck from the lower part of the city to the higher parts of the city where bike racks tend to empty out, Vélib incentivizes the returning of bikes to the hilly Montmartre area with free minutes for users.

The city has also capitalized on the brand-cool by selling Velib-inspired merchandize: everything from espresso mugs and iPhone cases to umbrellas and trendy shopping bags emblazoned with colourful sketches of the silver-grey, basket-clad bikes are for sale through Velib’s website.

Yearly memberships have also been kept surprisingly low, in fact the lowest among any major city. Vélib’s yearly cost is a mere €29 for adults, compared to £90 in London, $100 in Toronto, $95 in New York and €48 in Barcelona, with some of those cites already having experimented with, or considering, higher annual fees to cover the mounting costs associated with having to move bikes around, repair or replace them, and keep the system up to date. Velib is also among the cheapest for tourists, with a day rate costing only €1.70 and a week only €8.

The low cost for users might partly explain the high market penetration and user rates, but the financial sustainability of the system clearly comes down to the creative public-private partnership between the city and JCDecaux.

While it’s not clear if the city could earn more by selling billboard space itself and using the proceeds to fund Vélib, the current agreement would appear win-win-win, with happy private capital, money in the bank for Paris which can then use the proceeds on other city projects, and a low-cost alternative transport for city residents who benefit from a healthier lifestyle and cleaner air.

So are cities which rely on user-fees to generate profits doomed to failure? It’s yet to be seen if financial self-sufficiency, if that is what we want, can be achieved by charging higher costs to users.

Is Vélib’s sucess the model to follow? We might say the writing, or tire marks, are on the wall. JCDecaux has wasted no time, or advertising dollars, to get in on the action, and the company has quietly turned itself into a sought-out partner for turning around unprofitable programmes. The media giant is now operating bike-share systems in a diverse portfolio of 26 cities across France, Austria, Spain, Japan, Ireland, Australia, and other countries.

And there is evidence that JCDecaux will only enter an agreement if the terms suit their bottom line: recent negotiations with Helsinki, Finland fell through after the number of billboards offered was seen as insufficient by JCDeceaux to bring an attractive enough return. The coastal city has been without a bike sharing system since 2010, when its previous programme went bankrupt.

So can we only have bike-sharing if we plaster our cities with large billboard ads, cancelling out any environmental benefit of bike-sharing by promoting the consumption of automobiles and other Earth-taxing products?

There are a number of alternative, and more environmentally-forward, funding methods that could be initiated, such as having drivers pay for the system through tolls or increases in city-centre parking rates. But it seems that most cities, in the end, want their bikes, and to ride them too!