The focus of humanity has slowly shifted from biological evolution to socio-cultural revolution. Yet in spite of all our inventions, convenience appears to have turned its back on us, with cities indulged in traffic congestion, urban sprawl, air pollution, inaccessible shops & services, noise pollution and a host of other daily inconveniences. Very often, these problems are the result of bad planning.

In a city like Delhi, the capital of India, every individual wants a better standard of living. Quality of life appears to have been forgotten as a goal, potentially creating havoc in the years to come. Choked roads, overburdened public transport systems and poorly serviced neighbourhoods are making the lives of inhabitants unbearable. Yet enabling a modern city to survive, prosper and grow is incredibly complex. It is clear that things will not get better unless all the different urban stakeholders work together. Unfortunately, urban planning processes often emphasize the planning of land use in isolation from other sectors, ignoring the fact that cities are a set of systems interrelated and interdependent for efficient functioning.

Distributing low income housing evenly through a city or promoting owner-occupied housing developments in renter-occupied districts are two tactics Planners often used to reduce poverty in urban settlements. Unfortunately, these ‘solutions’ often bring varied and inconsistent results, failing to address the deeper socio-cultural and environmental forces that drive the urban system.

Let us assume that in a settlement there is a shortage of housing, which eventually leads to traffic congestion as people move between the city and the areas where they can find housing. This particular traffic congestion can be addressed in two ways:

Widening streets. This approach looks good in the short-term, but may eventually (and possibly quite quickly) worsen the situation.

Build more housing. The cross-sectoral approach would be to identify the real problem for traffic congestion, and therefore the solution to this traffic problem might be to build more housing. Identifying the root cause of the problem makes it easier to find a solution that enhances the quality of life for inhabitants, thus helping the urban ecosystem to work more efficiently.

This, of course, is only one example of how traffic congestion is caused (it’s not that easy!).

Another example can be found in the problem of depleted underground water levels, often caused by overly efficient urban systems that route surface run-off directly to disposal systems rather than allowing it to naturally penetrate the ground. Relying more on natural drainage systems will eventually lead to an increase in underground water levels as well as reducing the pressure on urban disposal systems, to some extent.

Natural processes are often misunderstood or not valued highly enough, which has also resulted in a degraded quality of air and water, despite these forming the basic need for the survival of humans.

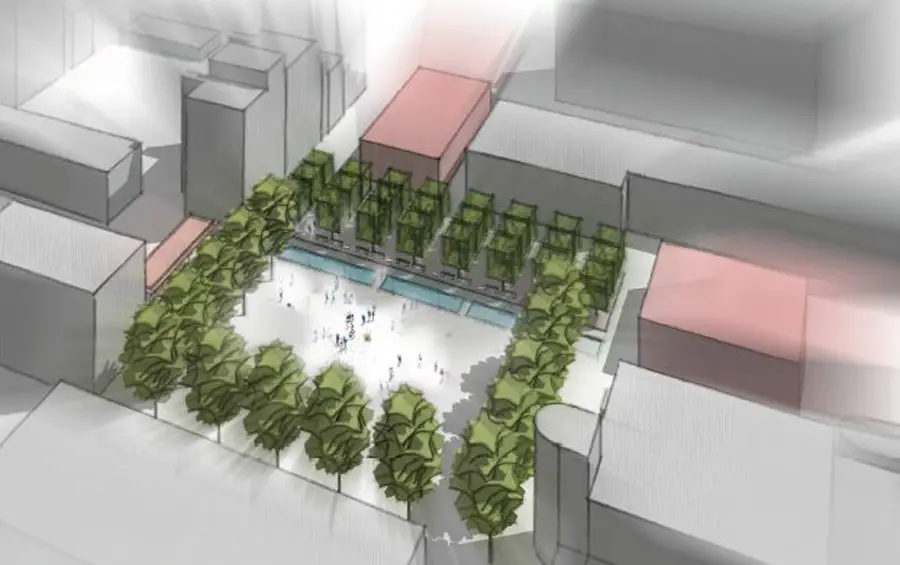

Cities (more specifically, urban settlements) can’t be developed and designed by planners, authorities and government organizations alone. Community involvement and participation is critical because it is this which governs the efficient functioning of the city on a daily basis. Cities are more of a biological phenomenon and hence it can be moulded around the needs and perception of the citizens inhabiting the space. The city is a gathering of people from diverse culture and regions, collectively forming the so-called ‘sub-cultures’ which constitute the basic feature of any urban settlement. The social aspect of cities is very important and planning such spaces which allow the formation and construction of the healthy societies should be one of a planner’s key concerns.

This much-discussed approach of participatory and inclusive planning needs to be exercised carefully and efficiently, however. This can only be achieved if urban planning evolves to include a truly multi-disciplinary approach, looking into the environmental issues, economics, sociology, cultural patterns, demographics, anthropometry, and the history of human settlements, to name just a few. Inevitably, many questions arise here:

- What should we do to be more efficient in implementing planning objectives?

- What can be learnt from past planning experiences?

- Do contemporary planning processes work, and if so, what should stay the same?

This approach could be considered a study of the science of human settlements. Things have changed in a big way in last few decades and this needs to be considered when trying to creating a happy urban environment based on human values.

Language facilitated the transmission of culture – the life ways of a group – from one generation to the other. Cultural adaptations have allowed the human race to spread across the globe. Yet the acceleration of developments that advanced humans over the last two centuries resulted in limited time to understand the phenomenon which humanity was undergoing. Prior to this, the phases were long enough and the developments were occurring at a comparatively slow rate, gifting humanity with sufficient time to understand them.

The human race used to maintain a balance with nature. But for the last two centuries, emphasis has switched to an expansion of area and infrastructure, leaving behind the standards of human existence, our natural behaviour and basic living values.

There is no doubt that humans have, by and large, evolved into a more prosperous society. However, now is the opportunity to learn from the mistakes we have made in order to improve basic living standards of all human lives. Contemporary planning approaches should explore the trends of human settlements, the characteristics of a human being, and the role of natural systems in creating cities that are good places for people to live in. Our current ignorance of these things has resulted in humanity paying a big price.

Jepranshu Aganivanshi is an architect, futurist and knowledge enthusiast living in New Delhi.

Photo: Matt Murf