As part of future-thinking initiative Earth 2.0, Melissa Sterry is aiming to re-establish a harmonious relationship between humanity and nature, something she believes cities are an integral part of. I was recently lucky enough to interview Melissa on the future of sustainable cities, and the challenges facing a rapidly urbanising Africa. Read on for the role of nature in cities, the potential of technologically equipped urban areas, and more:

Joe Peach: How critical are cities to Earth 2.0?

Melissa Sterry: Advanced civilizations are dependent on cities, as they hub together expertise and resources in an efficient and easily accessible fashion that enables citizens to get whatever needs doing done quickly. Unless humans develop Star Trek style teleportation devices or revert to a more primitive, nomadic existence, cities are imperative. Humans are not the only species that rely on cities, many insect species, including ants and termites, likewise rely on them. There are many parallel features that align human and insect cities, including division of space and labour, highways and technologies to regulate environmental conditions. In the event our Universe comprises other, equally, if not more advanced, civilizations than our own, they too will likely have adopted a city model. Therein, even before our earliest ancestors took their first steps on Earth, cities were vital and they will remain so for as long as intelligent life exists in all its myriad forms.

JP: If the world continues to urbanise as expected, what kind of future does Earth 2.0 envisage for rural areas?

MS: I do not believe that the world will continue to urbanise as expected, for change at a city, national and/or global scale is the consequence of many, often stochastic, therein unpredictable events. I think an Earth 2.0 approach to city and rural planning is nonlinear, so as to accommodate a wide range of possible future scenarios. I see today’s concrete jungles transformed into lush and biodiversity inclusive landscapes able to cope with diverse weather conditions and natural hazards. For example, I see tarmac replaced with both natural and Biomimetic surfaces that can absorb heavy downpours to mitigate flash floods and absorb heat to help prevent the urban heat island effect. I see both interior and exterior walls covered in vertical gardens, green roofs and urban farms, able to produce food, harvest water and energy and support biodiversity, while yet further enabling urban areas to regulate precipitation, heat and humidity. Animal and plant species, be it insects that pollinate flowers or trees that provide shade from the mid day sun, provide invaluable, highly cost-effective and efficient ecosystem services to cities. Therein, however the future unfolds, I think nature will reclaim her place in the city and the line between that which is urban and rural will become increasingly blurred as decades pass.

JP: How can we retrofit established cities on a large scale to make them more sustainable?

MS: The built environment 1.0 model presents significant challenges, of which I think the greatest is inflexibility. Today’s cities were not built to adapt, but to remain in a state of static inertia, regardless of any environmental changes taking place. Climatically, seismically and volcanically the past several thousand years have remained relatively stable, but past climate, seismic and volcanic records tell us that environmental stability is the exception, not the norm. These records also tell us of a strong possible link between climate change and increased seismic and volcanic activity. Emergent Earth 2.0 technologies that could enable our cities to cope with dynamic environmental changes include Biomimetic sensors, information networks, intelligent materials and dynamic architectures that create a conversation between buildings and their surroundings, such as the protocell technology being developed by my Earth 2.0 colleague Dr. Rachel Armstrong. Collectively these innovations could enable us to create smart cities; places able to not only monitor and regulate their resources, but able to anticipate environmental change and prepare for it.

JP: Sustainability appears to be less of a priority for governments tackling global economic recession. Can we reach earth 2.0 without government support?

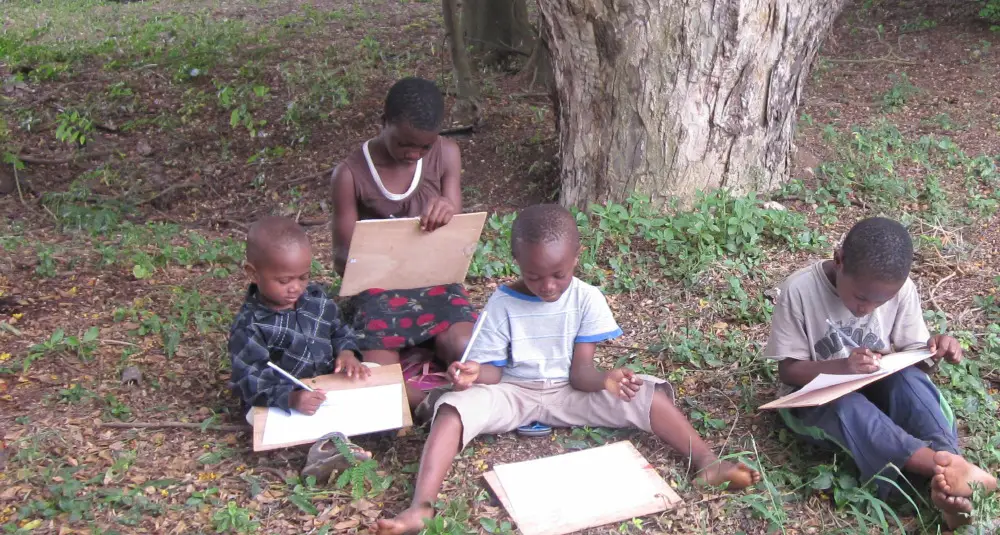

MS: Governments don’t lead revolutions. People do. The saying ‘Necessity is the Mother of Invention’ sums the scenario up, because most often it’s the individuals, communities and nations experiencing the toughest challenges that pioneer the most radical innovations. A few years ago I came across a project that involved providing remote impoverished communities in Africa with 3D printers. These communities had not banks, shops nor reliable supply chains. Therein, when their printer materials ran low, rather than buy new, the communities started recycling their own plastics, using whatever means available to them. When ‘needs must’ humans explore new ways of doing things. We never have and we never will need Governments to lead change. Can we reach Earth 2.0 without them? Not entirely, but we certainly can make a lot of headway, until such time as Governments whole-heartedly commit to prioritizing the creation of a sustainable society that will endure for future generations.

JP: Following the established growth pattern of cities is simple. How can we make it easier for developing cities to grow more sustainably, in a way most cities have failed to do so far?

MS: We can learn from nature. A few weeks ago an inspiring story broke about Aidan Dwyer, a 13-year old boy who has pioneered a more efficient way to arrange solar panels so that they generate 20-50% more energy than a uniform flat panel-array. Aiden’s invention was born of his observations of the Fibonacci sequence within tree growth. Five centuries ago the greatest known inventor of all time, Leonardo da Vinci, worked in exactly the same way. Amongst the many thousands of potentially world-changing innovations da Vinci imagined was the ‘Living City’: a metropolis modeled on a natural ecosystem. On the whole, Earth 1.0 cities expand chaotically, wherein infrastructure for everything from transport to sewage becomes increasingly laden until the point of failure. In stark contrast, ecosystems expand intelligently, wherein growth is organized around principles such as the Fibonacci sequence. Nature has already done much of the R&D needed to inform our Earth 2.0 cities, we just needed to take a closer look at her handy work.

JP: How can growing African cities cope with the likely developments brought about by climate change?

MS: The answers are in the backyard. Nature has learnt to turn the very hazards that humans label ’disasters’ into opportunities. Take for example flooding – many species in the Nile delta are dependent upon it, having built seasonal floods into their lifecycle. Water scarcity is no different, for many desert species, such as Namib desert beetle have evolved to overcome the problem, by means such as harvesting water vapor from the night air. Africa’s flora and fauna has pioneered solutions to every single challenge natural hazards pose, from heat waves to wildfires to dust storms to heavy precipitation. The answers are all there waiting to be found. Which highlights the importance of species conservation, because the moment a species become extinct we lose our ability to observe its behaviors and therein learn its secrets. Humans are not the only species that must adapt to the changes that lie ahead. Globally many land and sea species are on the move, from corals migrating towards the Poles to mountain trees scaling greater heights. Africa’s biodiversity will likewise need to shift and while some species, including flight-born insects and birds, will manage entirely on their own, others, particularly large mammals, will need help by the provision of migration corridors and habitat protection. Cities have a vital part to play in enabling this shift, be it ensuring that transport infrastructure, such as train routes and highways don’t cross major migration routes for the larger species, to providing havens for insect, bird, amphibian, reptile and small mammal species on the move. The challenge may be great, but to quote Sir David Attenborough “We can build a world, surely, where animals can have a home too.”

JP: What current examples of 2.0 thinking have you seen in today’s cities?

MS: Earth 2.0 cities need to be adaptable, which is why heat sink materials, which regulate interior temperatures in buildings, will play such a vital role. While thick walls can regulate interior temperatures passively, in a resource-stretched world we will need to do more with less, which is where BASF’s applied Micronal® a phase-change microcapsule technology comes in. The material comprises wax droplets encapsulated in acrylic microcapsules that absorb and release energy by melting and solidifying. Comprised of abundantly available materials, light weight to transport and reasonable to manufacture, this innovation embodies the term ‘smart material’. However, within just a few years, I anticipate the likes of BASF presenting even smarter materials, because chemistry and materials science is right at the frontline of combating climate change and other environmental hazards. I believe in the future, as is the case in nature, we’ll see man-made technologies multi-tasking from the molecular level upwards, therein the idea that a product performs one, not several tasks will become somewhat novel.