Sustainability activist Tia Kansara hopes for a future made up of cities that prioritise people and support nature. I was recently lucky enough to interview Tia on future urbanism, and how African cities can thrive, despite challenging natural conditions. Read on for how cities and rural areas can complement each other, how urban areas can adapt as the climate changes, and more:

JP: How critical are cities for the future of our planet?

Tia Kansara: Cities are growing to unprecedented sizes because people prefer to live in them. They are convenient spaces, which provide the city dwellers with access to a large variety of goods and services. Their growth is proportionately linked to the migration of rural inhabitants away from farms they tilled for hundreds of years. From their perspective this means more opportunity to move themselves away from poverty, but in the long run it is creating a sink in farming capability.

JP: If the world continues to urbanize as expected, what kind of future do you envisage for rural areas?

TK: Human beings are innately gregarious. They need to gather, relate to each other and have the security of a crowd with the acknowledgement of their peers. Our opportunities in the rural area lie in creating strong communities, thus giving a role to each member in producing food and shepherding the land so it does not become surplus to requirements.

Cities and rural areas compliment each other and cannot survive without the other. Cities are too concentrated to grow food for their inhabitants and therefore, rural areas serve two purposes for cities and all their dwellers – for food and recreation.

JP: How can we retrofit established cities on a large scale to make them more sustainable?

TK: Making the old urban fabric green by installing systems that do not waste energy. Providing adequate insulation according the climate to maintain thermal comfort whilst reducing the burden on energy from fossil fuels. The next 40 years will be a period of harvesting the sun, which is there for us, an unlimited supply of energy. If we can provide pipe runs for oil, there is no reason why we cannot move the energy of the sun to areas that do not experience as much sun. The huge deserts can become the future locations of solar harvesting. For example, the Sahara Desert could heat Europe.

Buildings cannot simply be boxes to house, entertain and employ people, they must, through their skin be used to produce agriculture. The roofs and walls must be intelligent enough to take rainwater, heat/cold and use this to benefit the immediate inhabitants in the buildings as well as those in the surroundings, using the public space in-between buildings.

JP: Sustainability appears to be less of a priority for governments tackling global economic recession. Can the planet become more sustainable without government support?

TK: Governments are there to change rules for the people. They must make tax schemes to encourage companies to fund the sustainable projects of the future. Further to this, they must empower people to participate in the process of becoming more sustainable citizens. They must also through their infrastructure encourage people to live a healthier lifestyle.

JP: Following the established growth pattern of cities is simple. How can we make it easier for developing cities to grow more sustainably, in a way most cities have failed to do so far?

TK: The twentieth century city has failed; they relied too much on the motorcar. Spaces for the first time in history for pedestrians exceeded their energy output. The only means from getting from A to B, particularly in a US scenario was by a car. New cities in developing countries must make sure their public transportation systems are in place at the cost of the individual motorcar. This means people have access to the whole city by affordable multi modal transport and mobility plans.

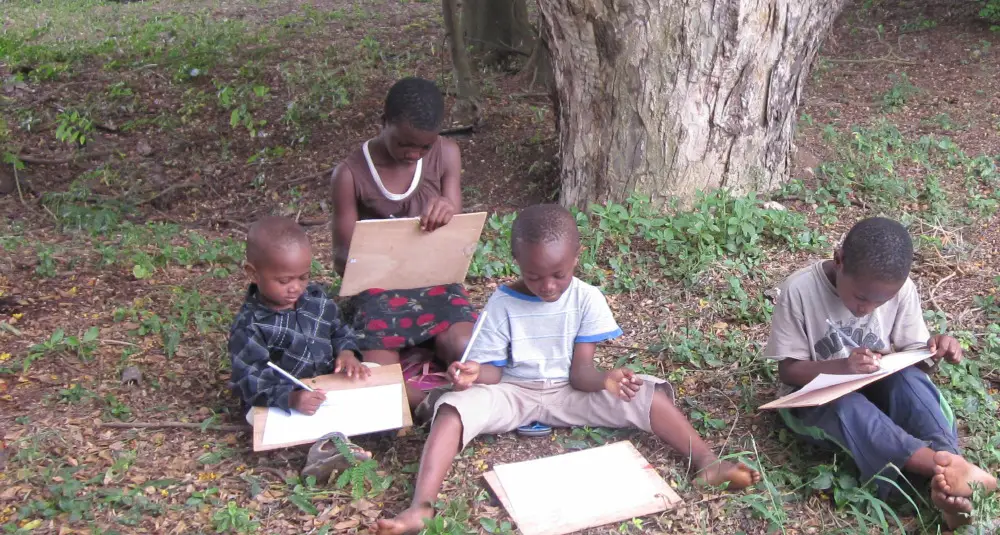

Within the 2050City we aim to have 50% of all food grown, gathered and distributed within the city boundaries. In addition, a city, which can have so much of its own agriculture in its boundary will be capable of freeing up a lot of energy that goes into importing food. Thus freeing up the city’s greatest asset – the productivity of its human inhabitants. Allowing them to instigate a vibrant, intellectual and productive economy away from fossil fuels. Intellectual includes learning institutions that become the research nucleus of cities.

JP: How can growing African cities cope with the likely developments brought about by climate change?

TK: Over the period of man’s habitation of the Earth, climate change has necessitated a migration. Today Africa is no different. Certain parts are becoming denuded because of the lack of water. Unless this water can be piped and cleaned, then some areas will become unsustainable for mankind. The conflict areas, with the lack of governance, for example, Somalia and old colonial boundaries – fixed for political rather than geographic or topographical considerations are still blighting the continent. Yet Africa has so many scarce resources as well as its beautiful animism.

African cities can produce good economic capabilities through good governance and sustainable cities. But this requires the support of the citizenry to ensure success. Johannesburg, Accra and Lagos could be exemplar of a large, modern African city. All blessed with access to sunshine, adequate water (if properly managed) and with learned and productive citizenry.

JP: What current examples of innovative thinking have you seen in today’s cities?

TK: The Community Architecture movement, where architects move into inner city areas, becoming long-term residents of run-down communities, pass on their skills and encourage residents to renovate their houses and environments through self-help, is one way, to avoid breakdown in civil order. When the local citizens have an investment in their community they will protect what they have invested their effort into. The recent urban riots in France, UK and USA may have been avoided had local people been entrusted in upgrading and maintaining their neighbourhoods.

The Permaculture and Transition Town networks, which encourage the introduction of agriculture into urban areas, are good examples of power coming back to the people. The Ukuvuna Urban Farm in Midrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, the Meanwood Valley Urban Farm in Leeds, UK and the Sustainable Agriculture and Urban Gardens programme in Havana, Cuba, are examples of the local urban population growing their own food. Again the residents protect what they have ownership in, and enjoy both reduced cost, but also healthier home produced food.