Regeneration by Shopping: Sheffield’s Missed Opportunity to Rethink City Development

When shopping centre developer Hammerson walked away from Sheffield’s much-vaunted New Retail Quarter last year, it could have been a blessing in disguise. Here was an opportunity to radically rethink the ‘mall without walls’ template for city centre regeneration.

Sheffield City Council’s chief executive, John Mothersole, has been quoted as saying that the next iteration of the long delayed retail quarter should be the ‘first of the new rather than the last of the old’.

It’s a neat turn of phrase that appears to acknowledge the profound changes that have taken place within retail and technology over the last decade. Instead of desperately wooing developers who are wedded to a late-20th century model of shopping centres, here was a chance to rewrite the book.

It hasn’t quite worked out like that. When the city council decided to press ahead with the development formerly known as Sevenstone, it was clear that while the circumstances had changed significantly, the thinking hadn’t. The objective, the council’s director of capital and major projects declared, was to ‘…deliver a New Retail Quarter that will fundamentally improve the retail offer in the city centre, by providing modern flexible retail floor plates and attracting quality fashion and accessories retailers, thus making a step change and lifting Sheffield back up the national retail ranking index’.

The council’s report went on:

‘The New Retail Quarter will provide a high class regional shopping and leisure facility which would compete with other city centres such as Manchester, Leeds and Nottingham. The scheme would drive private sector investment in the City Centre and create high quality retail and leisure led mixed use scheme and consolidate the prime retail offer. The development of a New Retail Quarter also enhances the status of the City Centre in itself and should in turn stimulate office, commercial and leisure opportunities/activity/development in the City Centre.’

This is a statement of faith in the same development orthodoxy that gave us the Westfield Hole in Bradford, has mooted the construction of a third shopping centre in Rochdale to address the lack of success of the first two, and that assumes regeneration can piggy-back on the increased spending of people whose incomes are static or falling in real terms.

The first of the new, it appears, could be very much along the same lines as the last of the old. Same big-brand shops, same big-name developers, same big-box thinking.

This week I was asked to provide some perspectives on high streets and trends in retail as an introduction to a workshop run by the Sheffield Society of Architects and Integreat Plus. The aim was to consider the area earmarked for the new retail quarter and examine how the existing masterplan might be revisited, looking at issues such as identity and distinctiveness, green space and the public realm, risk factors and timescales, and the mix of activities.

Shortly before the session I was forwarded a word of warning. It was revealing:

‘The main things governing the design are the development economics, the considerable cost difference between the type of scheme that most people with an interest in place would like to see and what those in the industry believe can actually be delivered.’

Architects and designers, it hinted, are prone to come up with expensive wishlists. What’s practical is what the development industry believes to be practical.

In my presentation I suggested there are two ways of thinking about what’s doable. One is the superimposition of approaches tried and tested elsewhere on whatever localities will support them – the Hammerson method. The frills and facades may vary, the mix of shopping and leisure may change, but the basic model is always a variation on the theme of a standard shopping centre anchored by a John Lewis, Marks and Spencer, Debenhams or suchlike. That’s what the industry considers doable, because that’s what the industry always does.

There is another way of thinking about what is doable. It is to start small and work with the grain; it is to build up from the micro rather than down from the macro. In development terms it is heresy. But in many places the big developers only move in once the interest and excitement has already been created by the small-scale occupiers of run-down and awkward spaces.

It is the development heretics who create value where value has evaporated. Take Renew Newcastle, which has brought life and occupancy to a host of empty shops in Newcastle, Australia, changing the reputation of the place to such an extent that Lonely Planet named it one of its top ten cities in 2011.

Marcus Westbury, Renew Newcastle’s founder, was recently invited to speak at Sheffield University. His talk drew on a long tradition of urban appreciation, the kind voiced 50 years ago by William H Whyte and Jane Jacobs. ‘What attracts people to places is interesting things,’ he said. ‘It’s people that attract people to places.’

You could describe that as a statement of the obvious. But in development terms it’s heresy: what attracts people to places, for much of the industry, is shiny new buildings and big brands.

I was curious to see which version of ‘doable’ those attending the Sheffield Society of Architects workshop would choose. They came up with a host of ideas and suggestions, some sweeping in scope and scale. But almost all of them focused on the need for flexibility, adaptability and variety: the kind of approach exemplified more by Kelvin Campbell’s ‘massive small’ than by development orthodoxies.

If the development of Sheffield city centre really is to be the first of the new, it needs to build on this shift from the big box to the fine grain. And unlike many cities, Sheffield has a heritage to build on: the ‘little mesters’ or craft workshops that fuelled Sheffield’s metalworking industries.

One of the main shifts technology has brought about is the ability to work on a micro and a global scale at the same time.Etsy can give a dressmaker working in a remote Scottish island access to a global marketplace; iTunes can do the same for musicians. The internet is all about choice and variety and flexibility. The very small can be amassed, mutated, and made accessible.

A retail centre that draws on Sheffield’s workshop heritage and technology’s global potential could create something genuinely different: making, selling, and inventing at both a micro and a macro level, enabling a multiplicity of occupants and occupations in city centre space. This could forge new models to complement what already exists elsewhere rather than desperately battling for trade with places that are already successful. Instead of seeking to compete on the retail rankings with Leeds, Nottingham and Manchester, could Sheffield tap into its own history of dissent and radical thinking to create something that really is the first of the new? Or would that be a heresy too far?

Julian Dobson is Director of Urban Pollinators and was co-founder and Editorial Director of New Start Magazine. He lived in east London for 16 years and tweets at @juliandobson.

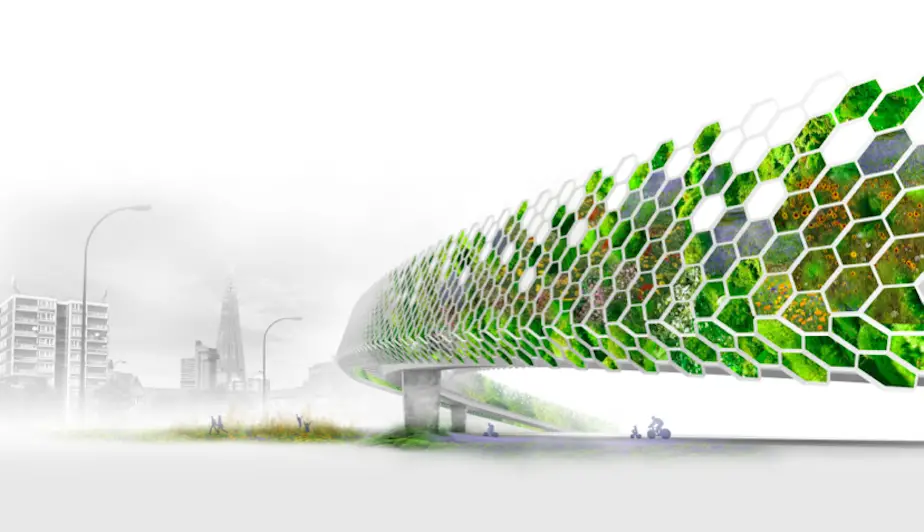

Image: Hawkins Brown.